Simple Grids#

General Concepts#

Most finite volume ocean models use Arakawa Grids, in which different variables are offset from one another and situated at different locations with respect to the cell center and edge points. As an example, we will consider C-grid geometry. As illustrated in the figure below, C-grids place scalars (such as temperature) at the cell center and vector components (such as velocity) at the cell faces. This type of grid is widely used because of its favorable conservation properties.

Layout of variables with respect to cell centers and edges in a C-grid ocean model. Image from the pycomodo project.#

These grids present a dilemma for the xarray data model. The u and t

points in the example above are located at different points along the x-axis,

meaning they can’t be represented using a single coordinate. But they are

clearly related and can be transformed via well defined interpolation and

difference operators. One goal of xgcm is to provide these interpolation

and difference operators.

We use MITgcm notation to denote the basic operators that transform between grid points. The difference operator is defined as

where \(\Phi\) is any variable and i represents the grid index.

The other basic operator is interpolation,

defined as

Both operators return a variable that is shifted by half a gridpoint with respect to the input variable. With these two operators, the entire suite of finite volume vector calculus operations can be represented.

An important consideration for both interpolation and difference operators is boundary conditions. xgcm currently supports periodic, Dirichlet, and Neumann boundary conditions, although the latter two are limited to simple cases, see Boundary Conditions.

The inverse of differentiation is integration. For finite volume grids, the

inverse of the difference operator is a discrete cumulative sum. xgcm also

provides a grid-aware version of the cumsum operator.

Axes and Positions#

A fundamental concept in xgcm is the notion of an “axis”. An axis is a group of coordinates that all lie along the same physical dimension but describe different positions relative to a grid cell. There are currently five possible positions supported by xgcm.

centerThe variable values are located at the cell center.

leftThe variable values are located at the left (i.e. lower) face of the cell.

rightThe variable values are located at the right (i.e. upper) face of the cell.

innerThe variable values are located on the cell faces, excluding both outer boundaries.

outerThe variable values are located on the cell faces, including both outer boundaries.

The first three (center, left, and right) all have the same length

along the axis dimension, while inner has one fewer point and outer has

one extra point. These positions are visualized in the figure below.

The different possible positions of a variable f along an axis.#

xgcm represents an axis internally using the xgcm.Axis class.

Although it is technically possible to create an Axis directly, the recommended way to

to use xgcm is by creating a single xgcm.Grid object, containing multiple axes

for each physical dimension.

Creating Grid Objects#

The core object in xgcm is an xgcm.Grid. A Grid object should be

constructed once and then used whenever grid-aware operations are required

during the course of a data analysis routine.

Xgcm operates on xarray.Dataset and xarray.DataArray

objects. A basic understanding of

xarray data structures is therefore needed to

understand xgcm.

When constructing an xgcm.Grid object, we need to pass an

xarray.Dataset object containing all of the necessary coordinates

for the different axes we wish to use.

We also have to tell xgcm how those

coordinates are related to each other, i.e. which positions they occupy along

the axis. We can provide this information in two ways: manually or via dataset

attributes.

Note

In most real use cases, the input dataset to create a Grid will be a

come from a netCDF file generated by a GCM simulation.

In this documentation, we create datasets from scratch in order to make the

examples self-contained and portable.

Manually Specifying Axes#

To begin, let’s create a simple example xarray.Dataset with

a single physical axis. This dataset will contain two coordinates:

x_c, which represents the cell center

x_g, which represents the left cell edge

We create it as follows.

In [1]: import xarray as xr

In [2]: import numpy as np

In [3]: ds = xr.Dataset(

...: coords={

...: "x_c": (

...: ["x_c"],

...: np.arange(1, 10),

...: ),

...: "x_g": (

...: ["x_g"],

...: np.arange(0.5, 9),

...: ),

...: }

...: )

...:

In [4]: ds

Out[4]:

<xarray.Dataset>

Dimensions: (x_c: 9, x_g: 9)

Coordinates:

* x_c (x_c) int64 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

* x_g (x_g) float64 0.5 1.5 2.5 3.5 4.5 5.5 6.5 7.5 8.5

Data variables:

*empty*

Note

The choice of these coordinate names (x_c and x_g) is totally

arbitrary.

xgcm never requires datasets to have specific variable names. Rather,

the axis geometry is specified by the user or inferred through the

attributes.

At this point, xarray has no idea that x_c and x_g are related to

each other; they are subject to standard

xarray broadcasting rules.

When we create an xgcm.Grid, we need to specify that they are part

of the same axis. We do this using the coords keyword argument, as follows:

In [5]: from xgcm import Grid

In [6]: grid = Grid(

...: ds, coords={"X": {"center": "x_c", "left": "x_g"}}, autoparse_metadata=False

...: )

...:

In [7]: grid

Out[7]:

<xgcm.Grid>

X Axis (periodic, boundary='periodic'):

* center x_c --> left

* left x_g --> center

The printed information about the grid indicates that xgcm has successfully

undestood the relative location of the different coordinates along the x axis.

Because we did not

specify the periodic keyword argument, xgcm assumed that the data

is periodic along all axes.

The arrows after each coordinate indicate the default shift positions for

interpolation and difference operations: operating on the center coordinate

(x_c) shifts to the left coordinate (x_g), and vice versa.

Detecting Axes from Dataset Attributes#

It is possible to avoid manually specifying the axis if the dataset contains

specific metadata that can tell xgcm about the relationship between different

coordinates.

If the autoparse_metadata kwarg is set to True (the default), xgcm looks

for this metadata in the coordinate attributes.

Wherever possible, we try to follow established metadata conventions, rather

than defining new metadata conventions. The main relevant conventions

are the CF Conventions, which apply broadly to Climate and Forecast datasets

that follow the netCDF data model, and the COMODO conventions and

SGRID conventions, both of which define

specific attributes relevant to Arakawa grids. While the COMODO conventions

were designed with C-grids in mind, we find they are general enough to support

all the different Arakawa grids.

Detection and extraction of grid information from datasets is performed by a series

of metadata parsing functions that take an xarray dataset and return a (potentially

modified) dataset and dictionary of extracted Grid kwargs.

When used as part of the autoparsing functionality of the Grid class there is a

default hierarchy imposed.

For more control a user can manually use a specific autoparsing function to extract

the Grid kwargs and then pass they to the Grid constructor (after any

changes/additions) with autoparse_metadata=False.

For example:

In [8]: grid = xgcm.Grid(ds)

coords = None

will return a Grid object constructed from xgcm’s best attempts to autoparse any

metadata in the dataset according to internal hierarchies, whilst

In [9]: ds = xr.Dataset(

...: {

...: "grid": (

...: (),

...: np.array(1, dtype="int32"),

...: {

...: "cf_role": "grid_topology",

...: "topology_dimension": 1,

...: "node_dimensions": "x_g",

...: "face_dimensions": "x_c: x_g (padding: high)",

...: },

...: ),

...: },

...: attrs={"Conventions": "SGRID-0.3"},

...: coords={

...: "x_c": (

...: ["x_c"],

...: np.arange(1, 10),

...: ),

...: "x_g": (

...: ["x_g"],

...: np.arange(0.5, 9),

...: ),

...: },

...: )

...:

In [10]: ds_sgrid, grid_kwargs_sgrid = xgcm.metadata_parsers.parse_sgrid(ds)

In [11]: grid = xgcm.Grid(ds, coords=grid_kwargs_sgrid["coords"], autoparse_metadata=False)

explicitly extracts SGRID metadata which is then used to construct a Grid object

without autoparsing.

SGRID data#

The identifier xgcm looks for is ‘SGRID’ in the conventions attribute.

Grid data is then contained within the variable with the cf_role of

‘grid_topology’.

A set of grid axes in the order 'X', 'Y', 'Z' are assigned based on the

dimensionality of the data.

Note that SGRID treatment of 3D grids and 2D grids with a vertical coordinate is

subtly different.

Both cases are handled by the autoparsing functionality to form a 3D Grid object.

SGRID ‘node_dimensions’ are extracted and correspond to xgcm’s cell edges. SGRID ‘face’ or ‘volume’ dimensions are then extracted with their associated ‘padding’ identifier. This corresponds to xgcm’s cell centers. Once the padding type has been extracted the correct xgcm ‘position’ can be assigned to the associated cell edge coordinate as set out in the following table:

SGRID padding |

position |

|---|---|

low |

right |

high |

left |

both |

inner |

none |

outer |

COMODO Data#

The key attribute xgcm looks for is axis.

When creating a new grid, xgcm will search through the dataset dimensions

looking for dimensions with the axis attribute defined.

All coordinates with the same value of axis are presumed to belong to the

same physical axis.

To determine the positions of the different coordinates, xgcm considers both

the length of the coordinate variable and the c_grid_axis_shift attribute,

which determines the position of the coordinate with respect to the cell center.

The only acceptable values of c_grid_axis_shift are -0.5 and 0.5.

If the c_grid_axis_shift attribute attribute is absent, the coordinate is

assumed to describe a cell center.

The cell center coordinate is identified first; the length of other coordinates

relative to the cell center coordinate is used in conjunction with

c_grid_axis_shift to infer the coordinate positions, as summarized by the

table below.

length |

|

position |

|---|---|---|

n |

None |

center |

n |

-0.5 |

left |

n |

0.5 |

right |

n-1 |

0.5 or -0.5 |

inner |

n+1 |

0.5 or -0.5 |

outer |

We create an xarray.Dataset with such attributes as follows:

In [12]: ds = xr.Dataset(

....: coords={

....: "x_c": (

....: ["x_c"],

....: np.arange(1, 10),

....: {"axis": "X"},

....: ),

....: "x_g": (

....: ["x_g"],

....: np.arange(0.5, 9),

....: {"axis": "X", "c_grid_axis_shift": -0.5},

....: ),

....: }

....: )

....:

In [13]: ds

Out[13]:

<xarray.Dataset>

Dimensions: (x_c: 9, x_g: 9)

Coordinates:

* x_c (x_c) int64 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

* x_g (x_g) float64 0.5 1.5 2.5 3.5 4.5 5.5 6.5 7.5 8.5

Data variables:

*empty*

(This is the same as the first example, just with additional attributes.)

We can now create a Grid object from this dataset without manually

specifying coords:

In [14]: grid = Grid(ds)

coords = None

In [15]: grid

Out[15]:

<xgcm.Grid>

X Axis (periodic, boundary='periodic'):

* center x_c --> left

* left x_g --> center

We see that the resulting Grid object is the same as in the manual example.

Core Grid Operations: diff, interp, and cumsum#

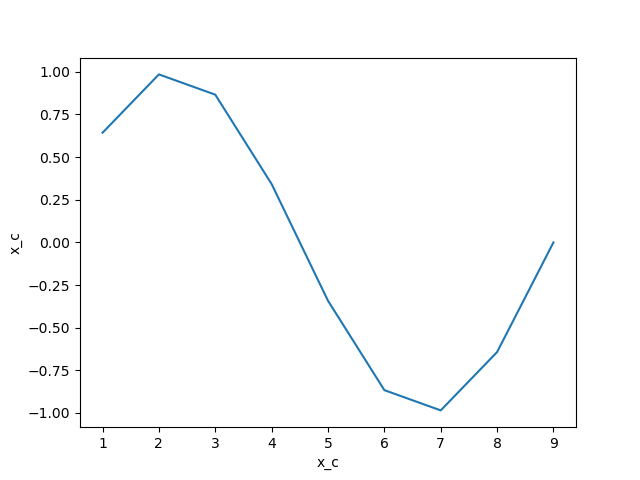

Regardless of how our Grid object was created, we can now use it to

interpolate or take differences along the axis. First we create some test data:

In [16]: import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

In [17]: da = np.sin(ds.x_c * 2 * np.pi / 9)

In [18]: print(da)

<xarray.DataArray 'x_c' (x_c: 9)>

array([ 6.42787610e-01, 9.84807753e-01, 8.66025404e-01, 3.42020143e-01,

-3.42020143e-01, -8.66025404e-01, -9.84807753e-01, -6.42787610e-01,

-2.44929360e-16])

Coordinates:

* x_c (x_c) int64 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

In [19]: da.plot()

Out[19]: [<matplotlib.lines.Line2D at 0x7f15695e37f0>]

In [20]: plt.close()

We interpolate as follows:

In [21]: da_interp = grid.interp(da, axis="X")

In [22]: da_interp

Out[22]:

<xarray.DataArray 'x_c' (x_g: 9)>

array([ 3.21393805e-01, 8.13797681e-01, 9.25416578e-01, 6.04022774e-01,

1.11022302e-16, -6.04022774e-01, -9.25416578e-01, -8.13797681e-01,

-3.21393805e-01])

Coordinates:

* x_g (x_g) float64 0.5 1.5 2.5 3.5 4.5 5.5 6.5 7.5 8.5

We see that the output is on the x_g points rather than the original x_c

points.

Warning

xgcm does not perform input validation to verify that da is

compatible with grid.

The same position shift happens with a difference operation:

In [23]: da_diff = grid.diff(da, axis="X")

In [24]: da_diff

Out[24]:

<xarray.DataArray 'x_c' (x_g: 9)>

array([ 0.64278761, 0.34202014, -0.11878235, -0.52400526, -0.68404029,

-0.52400526, -0.11878235, 0.34202014, 0.64278761])

Coordinates:

* x_g (x_g) float64 0.5 1.5 2.5 3.5 4.5 5.5 6.5 7.5 8.5

We can reverse the difference operation by taking a cumsum:

In [25]: grid.cumsum(da_diff, "X")

Out[25]:

<xarray.DataArray 'x_c' (x_c: 9)>

array([ 6.42787610e-01, 9.84807753e-01, 8.66025404e-01, 3.42020143e-01,

-3.42020143e-01, -8.66025404e-01, -9.84807753e-01, -6.42787610e-01,

1.11022302e-16])

Coordinates:

* x_c (x_c) int64 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

Which is approximately equal to the original da, modulo the numerical errors

accrued due to the discretization of the data.

By default, these grid operations will drop any coordinate that are not dimensions. The keep_coords argument allow to preserve compatible coordinates. For example:

In [26]: da2 = da + xr.Dataset(coords={"y": np.arange(1, 3)})["y"]

In [27]: da2 = da2.assign_coords(h=da2.y**2)

In [28]: print(da2)

<xarray.DataArray (x_c: 9, y: 2)>

array([[1.64278761, 2.64278761],

[1.98480775, 2.98480775],

[1.8660254 , 2.8660254 ],

[1.34202014, 2.34202014],

[0.65797986, 1.65797986],

[0.1339746 , 1.1339746 ],

[0.01519225, 1.01519225],

[0.35721239, 1.35721239],

[1. , 2. ]])

Coordinates:

* x_c (x_c) int64 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

* y (y) int64 1 2

h (y) int64 1 4

In [29]: grid.interp(da2, "X", keep_coords=True)

Out[29]:

<xarray.DataArray (x_g: 9, y: 2)>

array([[1.3213938 , 2.3213938 ],

[1.81379768, 2.81379768],

[1.92541658, 2.92541658],

[1.60402277, 2.60402277],

[1. , 2. ],

[0.39597723, 1.39597723],

[0.07458342, 1.07458342],

[0.18620232, 1.18620232],

[0.6786062 , 1.6786062 ]])

Coordinates:

* x_g (x_g) float64 0.5 1.5 2.5 3.5 4.5 5.5 6.5 7.5 8.5

Dimensions without coordinates: y

So far we have just discussed simple grids (i.e. regular grids with a single face). Xgcm can also deal with complex topologies such as cubed-sphere and lat-lon-cap. This is described in the grid_topology page.